A workers’ compensation claim may have significant negative impacts on an injured worker’s wellbeing. Wellbeing provides a good global measure of potential effects of a claim on an individual, and is important for contemporary economic modelling. The purpose of this study was to synthesize knowledge about the wellbeing of injured workers after the finalization of a workers’ compensation claim and identify gaps in the current literature.

A systematic scoping review was conducted.

71 full-text articles were screened for inclusion, with 32 articles eligible for this review. None of the included articles evaluated overall wellbeing. Included articles did evaluate a variety of constructs inherent in wellbeing. Injured workers were generally disadvantaged in some manner following claim finalization. The literature recommends a focus on reducing negative impacts on injured workers after finalization of a compensation claim, with a need for regulatory bodies to review policy in this area.

There appears to be potential for ongoing burden for individuals, employers, and society after finalization of a workers’ compensation claim. A gap in knowledge exists regarding the specific evaluation of wellbeing of injured workers following finalization of a workers’ compensation claim.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Good work is beneficial for health and wellbeing [1, 2]. The primary purpose of most modern workers’ compensation schemes is to support injured workers financially and/or with medical care following a work-related injury or disease. Workers’ compensation systems may also assist injured workers to return to their pre-injury level of work, before considering alternative pathways such as suitably modified or alternative employment. In the 2019–2020 reporting period in Australia, 115,707 serious injury claims involving at least one working week-off work were accepted [3]. The burden of these injuries is evident in the duration of a workers’ compensation claim, which was 537 days on average, between 2019 and 2021 in Australia [4]. Despite this, most injured workers in Australia (81.3%) returned to some degree of work following their injury and continued to be in paid employment of some description [5], which is consistent with other similar jurisdictions internationally [6, 7]. This also is indicative of approximately 20% of injured workers, who do not return to paid employment following their injury.

Wellbeing is experienced when an individual is engaged in pursuing meaningful goals and has an opportunity to realize their potential [8]. The World Health Organization states that “Well-being encompasses quality of life and the ability of people and societies to contribute to the world with a sense of meaning and purpose” [9]. Importantly, it acknowledges not only the negative aspects of ill health, but also the positive aspects of living. In this way, wellbeing at the individual level can be broadly considered as encompassing our physical and mental health, relationships, the quality of our work and job satisfaction, political and spiritual freedom, and our physical environment [10] (Fig. 1). The concept of wellbeing is also becoming more important for contemporary economic modelling (the wellbeing economy) [11] (Fig. 1).

Participation in a workers’ compensation claim can negatively affect wellbeing in multiple ways [12, 13]. Aurbach [14] posits that exposure to a compensation claim can result in altered, unhelpful behaviours and “needless disability”. Caruso [15] describes that “worklessness” is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, as well as negative psychological, social, and economic effects on an individual, their family, and their community [15]. Other systemic impacts during a claim can include medicalization (the process through which some aspects of human life, which were not previously pathologized, come to be considered as medical problems) [16], and iatrogenesis (the intentional or unintentional harm that comes to a person through the action or inaction of a health care provider or health delivery system). This may be immediate or delayed, yet preventable or even avoidable [17]. Complex administrative systems, independent examinations, legal representation, and adversarial environments are elements of a workers’ compensation claim associated with loss of control, which can have a negative impact on wellbeing [14, 18, 19]. Ultimately these issues might result in sub-optimal functional and psychological outcomes [20]. A systematic review of 29 studies from a range of international compensation jurisdictions supports this view, describing an association between having a claim and poorer physical and psychological functioning [21]. An evaluation on the effects of financial compensation for workplace injuries in Australia reported that injured workers receiving workers’ compensation were vulnerable to financial stress [22]. Kilgour et al. [23] also identified in a systematic review of qualitative studies, a “growing consensus that involvement in compensation systems contributes to poorer outcomes for claimants” (p. 160). Workplace culture and satisfaction, as perceived by the injured worker, can also negatively influence return to work outcomes following workplace injury [24]. Management of musculoskeletal conditions is associated with poorer outcomes in workers’ compensation settings [14, 15, 25]. For injured workers who do experience negative influences during their compensation claim, it is plausible that their wellbeing might continue to be affected beyond the finalization of the claim [7].

There are a range of different modes of claim finalization which vary with the jurisdictions within and between countries. Typically, claim finalization may be implemented for the following reasons: (1) an individual is deemed to have met the criteria for a successful medical recovery and returned to pre-injury employment or alternative employment; (2) the designated time limit for a compensable period is reached; (3) an agreement is reached between an individual and an insurer to exit the claim environment, and an appropriate negotiation for ongoing support (if applicable) outside the claim is undertaken; (4) an approved medical specialist assesses and deems that an individual has reached Maximum Medical Improvement which may be at a level less than full medical recovery, resulting in determination of a permanent impairment which may attract a prescribed or statutory amount of financial compensation; (5) a claim is finalized via legal avenues; or (6) compensation entitlements are exhausted. Different jurisdictions will utilize differing terminology to indicate the end-point of a compensation claim period. In some jurisdictions, a claim may be considered inactive, rather than settled or finalized. The needs and wellbeing outcomes of individuals returning to work and life once they leave the system are not well understood. Poorer post-claim outcomes may lead to further health and social burden on injured workers, and increased demands on health and social service/welfare systems [26,27,28].

The end of a workers’ compensation claim is not always associated with full recovery or return to work. Negative outcomes for employment and function have been noted even up to 5 years following claim settlement [29]. In addition, there is some indication that post-claim outcomes might be worse for those who are already socially disadvantaged [30, 31]. In general, however, literature investigating the health, financial, and employment status of individuals after finalization of a claim appears limited, and there is certainly no consolidated body of knowledge on this topic. Wellbeing is an important measure for community-based social support systems such as workers’ compensation [32, 33], but post-claim wellbeing outcomes are unclear. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to review the literature in relation to wellbeing and other associated outcomes of individuals following finalization of a workers’ compensation claim and identify gaps in the literature related to this.

A systematic scoping review was deemed a suitable methodology for this study [34]. The review aimed to identify the types of available evidence related to the purpose of the study, to examine how research is conducted in this field, to describe key characteristics of wellbeing and other outcomes following finalization of a workers’ compensation claim and to identify gaps in our understanding of life following a workers’ compensation claim. Established frameworks for scoping reviews were used to inform the processes taken in completing the review [35, 36]. The review has been reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) [37]. Prior to undertaking the database search, the Scoping Review protocol was submitted for registration on the Joanna Briggs Institute Review Register (https://jbi.global/systematic-review-register, registration date 17th March 2022).

The participants of interest were adults aged over 18 years, who had engaged in, and subsequently finalized a workers’ compensation claim or ceased engagement with the insurer. As different jurisdictions utilize varied terminology or system-based definitions to delineate the end-point of a workers’ compensation claim process, a range of terminologies were considered in the search strategy (Appendix 1).

The concept of the scoping review was to understand the experience of individuals following finalization of a workers’ compensation claim. Wellbeing was the primary focus of interest because of the potential effect of a workers’ compensation claim extending beyond impacts on physical capability, mental health status, and health-related quality of life. Also, there is increased recognition of the importance of wellbeing as a multi-dimensional adjunction to traditional economic measures of social programs [38]. However, the research team anticipated that the literature on the specific concept of wellbeing was likely to be limited in the literature. Hence, individual constructs of wellbeing such as financial status, employment status, health status, quality-of-life status, and relationship status were incorporated in the search strategy (Appendix 1).

The context was settings where individuals had engaged in, and subsequently finalized or ceased engagement with, a workers’ compensation insurance claim in a jurisdiction with a legal and regulated workers’ compensation scheme.

The review considered English language quantitative studies, qualitative studies, mixed-method studies, and online resources.

Research that considered wellbeing, or constructs of wellbeing, in injured workers aged 18 years or older, following the finalization of a workers’ compensation claim in a regulated workers’ compensation scheme was included. All study designs and papers written in English were included for consideration.

The literature was excluded if published in languages other than English, or if there was no clear indication of a workers’ compensation claim having ended. Conference papers, editorials, and review articles were excluded.

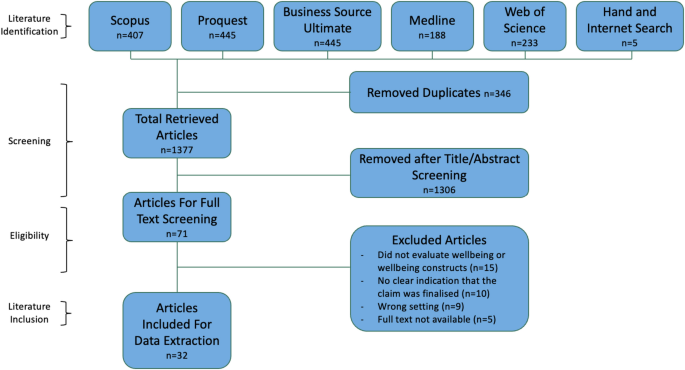

The initial step utilized the assistance of the Curtin University Librarian to develop a limited search of broad multidisciplinary databases including Scopus and Proquest as well as a medical database Medline (Pubmed). The aim was to discover literature where specific measures of wellbeing had been included, as well as literature that included individuals’ experiences and health or social outcomes following claim finalization. The abstracts were screened to evaluate relevant search terms or keywords that should be included in the final search. Once the final search terms were confirmed, a search was carried out in all included databases; Scopus, Proquest, Business Source Ultimate, Medline (Pubmed) and Web of Science. These databases were selected due to their broad, multidisciplinary natures, to allow for medical, social, and legal forums to be explored. The date range utilized was from 1884 (considered the inception of modern workers’ compensation insurance under Prussian leader Otto von Bismarck [39]) to November 2022.

Further hand searching of the reference lists of the 32 included articles was carried out to identify additional relevant published literature for inclusion. The scoping review also included internet searching, to identify online information sources, reports, media releases, or websites that considered wellbeing, or constructs of wellbeing in injured workers, following finalization of a workers’ compensation claim. The search terms were inputted verbatim into web-based searching using Google and Google Scholar. Further to internet-based searching, specific exploration of jurisdictional regulatory websites was also undertaken. This included the states of New South Wales and Victoria in Australia, Ontario in Canada, and Missouri, California, and Washington State in the United States of America, as well as Sweden and Taiwan, as these were the jurisdictions represented in the included articles. In addition to this, further internet searching of jurisdictional regulatory websites was undertaken in the United States of America, Canada and Australia.

Suitable literature was exported to EndNote® before being assessed for duplicates and exported to Covidence® (http://www.covidence.org) for title and abstract screening. Abstract screening was completed independently by two researchers (JW and MG), to select appropriate literature, with any disagreements being resolved by a third reviewer (DB).

This was then followed by full-text review for suitability using Covidence® independently by two researchers (JW and MG) to select the final literature for inclusion, with any disagreements being resolved by a third reviewer (DB).

A data extraction template was developed within the Covidence® software. Initial extraction on the first 20% of the articles was performed independently by two researchers (JW, MG) to check for consistency and suitability of the extraction process. JW, MG and DB reviewed the quality of the data being extracted, modified the extraction template to include participant characteristics and the time since claim finalization, and refined the labelling of the extracted data. The final data extraction framework included the study characteristics (design, geographical location, the injury type being evaluated), characteristics of the participants (number, time since claim finalization, age, sex), measures of overall wellbeing or other specific wellbeing constructs, key findings, and any recommendations made by the authors. JW completed extraction of all the data, with assistance and review from DB.

Critical appraisal is not an essential component of the scoping review process and in accordance with guidelines can be included as an optional step in the process [37]. In order to provide the reader with an understanding of the characteristics of the literature in this area, critical appraisal of the final 32 included articles was completed utilizing the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools, relevant to each study design. Despite being designed for use in systematic reviews, these tools are also endorsed as an educational tool [37]. These tools do not provide a grade of quality, rather serve to facilitate an understanding of methodology of the studies included in the review and are used at the discretion of the research team [40]. Critical appraisal was completed on 20% of the articles by two independent researchers (JW, MG). The level of agreement was validated by a third researcher (DB). JW then completed critical appraisal of the remaining articles.

The results of the article inclusion process are depicted in Fig. 2. The data search retrieved 1723 articles, 5 of these from additional hand searching of the included articles and internet-based searching. Following removal of duplicates and title and abstract screening, 71 articles were included in full-text screening. Following full-text screening, a total of 32 articles were included for extraction [29,30,31, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69]. The articles ranged in time of publication from 1970 to 2022. A large proportion of the articles were completed by a small range of research teams and authors. Two people were authors on 8/32 articles (Chibnall and Tait). Another person (Sears) was an author on 7/32 articles, all 7 of which were published in 2021 and 2022. Terms used to denote claim finalization were permanent impairment/disability (26/32), settlement (14/32), claim/case closure (13/32), and lump sum (4/32). Data extracted from each study are provided in Table 1.

Results of the critical appraisal are presented in Appendices 5–8.

This scoping review identified 32 articles that assessed aspects of wellbeing in injured workers who had finalized a workers’ compensation claim and synthesized knowledge on this topic. No study specifically measured overall wellbeing as an independent construct through the use of specific measures [72,73,74]. One article did refer to a concept of ‘long term adjustment’ as an umbrella term encompassing individual measures of pain, disability, catastrophising, long-term unemployment, and reliance on social security [31]. This concept of long-term adjustment might be akin to the concept of wellbeing. More generally, injured workers who had finalized a workers’ compensation claim had ongoing negative consequences from the claim at an individual level [43, 51, 54,55,56,57, 69]. When comparisons were made to the general population, injured workers post-claim appeared disadvantaged in multiple ways which arguably reflect reduced wellbeing and greater cost burden to their communities [43, 47, 51, 57,58,59,60,61, 64, 65]. It is important to note though that most of the cases in this review had finalization of their claim defined by permanent impairment/disability (for a musculoskeletal complaint), so by definition of permanent impairment/disability, injured workers in these cases are likely to experience ongoing issues related to physical health.

This study utilized a robust design and procedure informed by established frameworks and reporting standards for scoping reviews [35,36,37]. This included using the services of a librarian, searching multiple database repositories from broad subject areas and using multiple investigators in the literature review and data extraction processes. The research team included academics and practitioners with broad research and clinical experience in workers’ compensation, occupational medicine, physical rehabilitation, law, and wellbeing. This mix of contributors provided a breadth of knowledge and interpretation befitting the nature of the review.

A limitation may have been restricting the scope of the hand searching and online literature search to local regulatory websites and handsearching of reference lists of the included articles. The majority of articles were from North American workers’ compensation schemes and may not be representative of other parts of the world. The wide date range of the final included papers is representative of the current literature base. However, potential changes in workers’ compensation system over this time period were not considered in the review. Further research might investigate the effect of legislative change on worker outcomes. There is no universal language for finalization of a claim, and our definition of this concept might have potentially limited the search. Further, with most of the included studies being defined by permanent impairment/disability, the findings might not reflect what occurs after claim finalization where most claims are of short duration with minimal disruption to work [75]. Nevertheless, future burden to society is more likely to result from finalized claims with a permanent impairment awarded and/or when there has been significant time off work.

It is well documented that a workers’ compensation claim can have significant negative effects on some injured workers during a claim [14, 15, 23, 76]. The findings of this scoping review support the proposition that this burden on injured workers can continue after claim finalization. These findings are contrary to earlier medico-legal assertions, often frequently cited by insurers that the finalization of a workers’ compensation claim will result in positive outcomes for all injured workers [77,78,79,80,81]. While this review did not identify any studies directly assessing wellbeing, it did identify a range of impacts on physical and psychosocial or behavioural health post-claim. Contemporary practice for the management of injured workers during a compensation claim demands a biopsychosocial approach [25, 82], to maximize integration back into work. The progression over recent decades towards workers’ compensation systems that promote workplace rehabilitation and wider ranging health supports (including support for mental health) beyond financial compensation is in keeping with the biopsychosocial approach [83]. Injured workers who were engaged in structured vocational rehabilitation and had supportive workplace environments during their claim were more likely to experience less interruptions to work post-claim [59, 61]. This supports the importance of a biopsychosocial approach to claim management and the transition back to life after claim finalization. Similarly, the ongoing management of people following a claim is likely to need broad biopsychosocial approaches.

Wellbeing has increasingly become a favoured term and metric associated with government policy making and planning [38, 84, 85] (Fig. 1), and this may help quantify the nature of the economic burden that results from workers’ compensation claims. Disruption of individual wellbeing during a claim that endures beyond claim finalization may have societal implications. Cost shifting (from workers’ compensation schemes to other public services) may be one issue. For example, when financial support provided under a compensation claim is withdrawn (though the claim is not closed), people may go on to receive social security payments [26, 28] and publicly provided health care [27]. Further issues may include ongoing deterioration of personal relationships and social networks. The findings of this scoping review indicate that this broader societal impact conflicts with the concepts of a wellbeing economy that promotes “dignity, connection, fairness, and participation” [11] (p. 5). However, the ongoing burden and potential cost-shifting following the end of a claim may be difficult to quantify as people transition from well-monitored compensation schemes [3, 4] to environments where the lasting impact on wellbeing due to the claim is not monitored. Consequently, wellbeing may be a valuable collective measure of these impacts for individuals and the broader community.

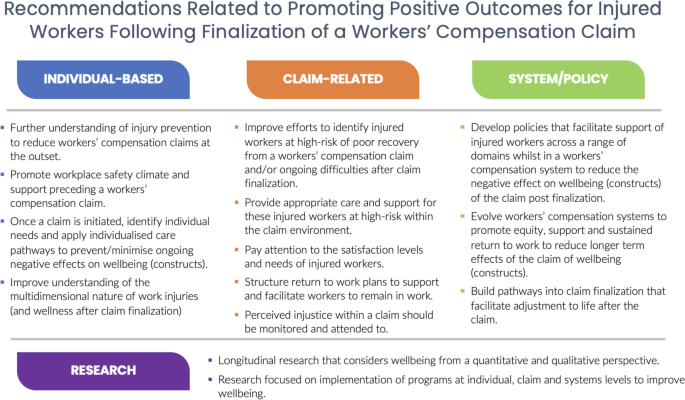

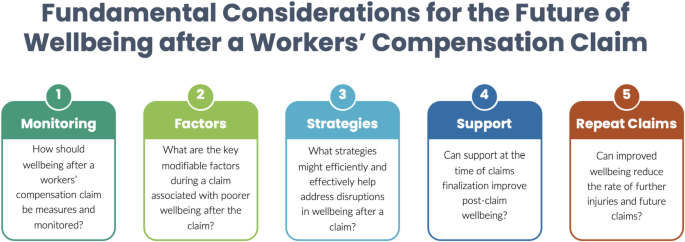

Addressing wellbeing directly could have positive effects for the individual and society as a whole. This should be a consideration during a claim, at the time of finalization and beyond finalization. A broad array of recommendations at individual, claim, and system/policy levels, have been identified in this scoping review (Fig. 3). It may be pertinent for researchers, schemes, and service providers to consider global initiatives to which these recommendations align (Fig. 4). Increased understanding of individual wellbeing following the end of a workers’ compensation claim is needed. Ultimately this might guide scheme reforms and assist with the development of programs and resources for enhancing wellbeing following finalization of a workers’ compensation claim.

The workers’ compensation environment has been demonstrated to be an important environment for implementation of interventions and strategies to facilitate outcomes within the life time of the claim [48, 86,87,88,89,90]. Further understanding and measurement of these outcomes beyond the end-point of the claim may help determine if these outcomes continue, and whether these outcomes influence individual wellbeing and broader society following claim finalization. In addition, there was a notable absence in consideration of the lived experience, beliefs, and attitudes of injured workers around this critical transition period. Individuals’ beliefs and attitudes are considered to be an integral part of broader behavioural health [91]. A better understanding of the beliefs and attitudes of injured workers may facilitate a better understanding of the needs of these individuals and may provide a compass for developing and implementing person-centred support. It is not clear with whom the responsibility lies for collecting and evaluating this data and clarifying this duty is considered an important step in further research.

Transitional support for injured workers following claim finalization is an important consideration that has been implemented and reviewed in this population but has not been evaluated in depth in the existing literature base [26,27,28]. Understanding whether or not transitional support influences the wellbeing of injured workers following the finalization of a claim may facilitate further decision making regarding the most appropriate pathways to support injured workers through this process. Furthermore, there is not a clear understanding of the influence of multiple or recurrent claims on the wellbeing of injured workers following claim finalization. This was previously identified as an understudied phenomenon in the occupational literature [48]. Knowledge in this area may also guide designation of appropriate support measures that are specifically tailored to the needs of injured workers.

This scoping review has synthesized a body of literature that evaluates outcomes of injured workers following the end of a workers’ compensation claim. Disruption to wellbeing as a result of engaging in a workers’ compensation claim appears to have implications that last well beyond claim finalization. There appears to be potential for ongoing burden for individuals, employers, and society after finalization of a workers’ compensation claim. Further research that examines the specific nature of wellbeing after finalization of a workers’ compensation claim is warranted.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The primary author James Weir is undertaking a PhD program at Curtin University which is supported by a Commonwealth Government Higher Degree by Research scholarship.